Queues‚ fundamental data structures‚ mirror real-world waiting lines‚ adhering to the First-In‚ First-Out (FIFO) principle for efficient element management.

What is a Queue Data Structure?

A queue is a foundational data structure designed to manage a collection of elements in a specific order. It operates under the principle of First-In‚ First-Out (FIFO)‚ meaning the first element added to the queue will be the first one removed. This contrasts with stacks‚ which follow a Last-In‚ First-Out (LIFO) approach.

Essentially‚ a queue is a linear list where additions occur at one end – the ‘rear’ – and removals happen at the opposite end – the ‘front’. This structured approach makes queues incredibly useful in scenarios where maintaining order is crucial. They are characterized by two primary ends‚ facilitating controlled access and manipulation of the stored data. Understanding this fundamental concept is key to grasping the broader applications of queues in computer science.

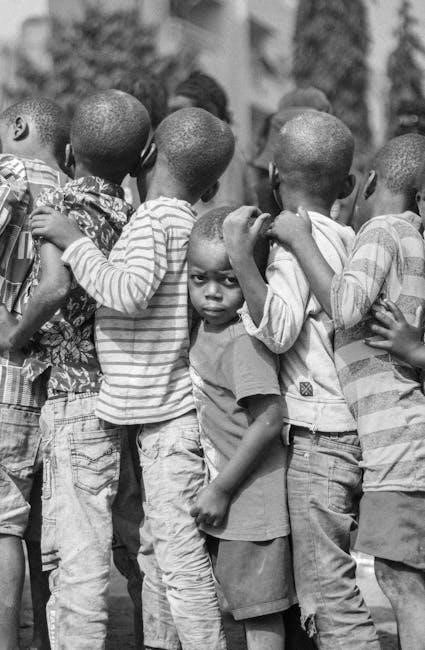

Real-World Analogy: Waiting in Line

Imagine standing in a line at a cinema or a supermarket – this perfectly illustrates a queue! The first person to join the line is the first to be served‚ embodying the FIFO (First-In‚ First-Out) principle. Newcomers join the back of the line‚ while those at the front are processed and leave.

This everyday scenario mirrors how a queue functions in computer science. Just like in a physical line‚ elements enter at one end (the rear) and exit from the other (the front). This simple analogy helps visualize the orderly nature of queues and their ability to manage tasks or data in a sequential manner. The concept of fairness and order inherent in waiting lines directly translates to the functionality of this essential data structure.

FIFO (First-In‚ First-Out) Principle

The cornerstone of queue operation is the FIFO (First-In‚ First-Out) principle. This means the very first element added to the queue will be the very first one removed. Think of it like a pipe: whatever goes in first‚ comes out first – there’s no skipping or rearranging. This contrasts sharply with other data structures like stacks‚ which operate on a LIFO (Last-In‚ First-Out) basis.

This principle ensures fairness and order in processing. Elements are handled in the sequence they were received‚ preventing starvation or prioritization unless specifically implemented in a priority queue. The FIFO method is crucial for applications where maintaining the original order of data is paramount‚ such as task scheduling or managing requests in a server environment. It’s a fundamental concept defining the behavior of a queue.

Core Concepts of Queue Operations

Queue operations revolve around enqueue (adding elements) and dequeue (removing elements)‚ alongside accessing the front and rear for data management.

Enqueue: Adding Elements to the Rear

Enqueue is the fundamental operation for adding new elements to a queue. Conceptually‚ it’s akin to a person joining the back of a waiting line. This process involves placing the new element at the rear end of the queue‚ increasing the size of the queue by one.

In practical implementation‚ whether using an array or a linked list‚ the enqueue operation requires updating pointers or indices to reflect the new element’s position. For array-based queues‚ this often involves incrementing a rear index. With linked lists‚ a new node is created‚ and its ‘next’ pointer is set to null‚ then linked to the previous rear node.

Successful enqueue operations depend on available memory or space within the queue. If the queue is full (in the case of a fixed-size array)‚ the enqueue operation may fail or require resizing‚ depending on the implementation. Proper error handling is crucial to maintain queue integrity.

Dequeue: Removing Elements from the Front

Dequeue is the operation responsible for removing the element that has been in the queue the longest – the one at the front. Imagine the first person in a line being served and then leaving; that’s dequeue in action. This process reduces the queue’s size by one.

Implementation varies based on the underlying data structure. For array-based queues‚ dequeue typically involves shifting all remaining elements forward to fill the gap left by the removed element‚ or adjusting a front index. With linked lists‚ dequeue is simpler: the front node is unlinked‚ and its memory is reclaimed.

A critical consideration is handling empty queues. Attempting to dequeue from an empty queue results in an error (underflow) and requires appropriate error handling to prevent program crashes. Efficient dequeue operations are vital for maintaining queue performance.

Front: Accessing the First Element

The front of a queue represents the position of the element that has been waiting the longest – the next one to be removed via a dequeue operation. Accessing the front element allows you to inspect its value without actually removing it from the queue. This is crucial for various applications where you need to know what’s next in line.

How you access the front depends on the queue’s implementation. In an array-based queue‚ this is typically done by accessing the element at the index designated as the front. With a linked list implementation‚ accessing the front involves retrieving the data from the node pointed to by the front pointer.

It’s important to note that attempting to access the front of an empty queue will result in an error‚ similar to attempting a dequeue on an empty queue. Proper error handling is essential.

Rear: Accessing the Last Element

The rear of a queue signifies the position where new elements are added‚ or enqueued. Accessing the rear element allows inspection of the most recently added item without removing it. This functionality is less commonly needed than accessing the front‚ but can be useful in specific scenarios‚ such as monitoring the latest entry.

Similar to accessing the front‚ the method for accessing the rear depends on the queue’s underlying implementation. In an array-based queue‚ this involves accessing the element at the index designated as the rear. For a linked list implementation‚ it means retrieving the data from the node pointed to by the rear pointer.

Care must be taken to avoid errors; attempting to access the rear of an empty queue will lead to an error. Robust error handling is vital for reliable queue operations.

Types of Queues

Queues come in diverse forms – simple‚ circular‚ priority‚ and dequeue – each optimized for specific applications and offering unique operational characteristics.

Simple Queue: Basic Implementation

The simple queue represents the most straightforward approach to implementing the queue data structure. It functions on the core FIFO (First-In‚ First-Out) principle‚ where the first element added is the first one removed. Typically‚ this is achieved using an array or a linked list as the underlying storage mechanism.

In an array-based implementation‚ a fixed size is usually allocated beforehand. Elements are added to the rear of the array‚ and removed from the front. However‚ this can lead to inefficiencies if the array becomes full or if many elements are removed‚ leaving empty spaces at the beginning. A linked list implementation overcomes this limitation by dynamically allocating memory for each element‚ allowing for more flexible growth and shrinkage.

Basic operations like enqueue (adding an element) and dequeue (removing an element) are implemented by manipulating pointers or indices within the chosen storage structure. While simple to understand and implement‚ this basic form may not be the most efficient for all scenarios‚ particularly those requiring frequent resizing or prioritization.

Circular Queue: Efficient Memory Utilization

The circular queue addresses a key limitation of the simple queue’s array implementation: inefficient memory usage. In a standard array-based queue‚ removing elements can leave empty spaces at the front‚ even if the queue isn’t logically full. A circular queue solves this by treating the array as if its ends are connected.

When the rear reaches the end of the array‚ it wraps around to the beginning‚ reusing the space vacated by dequeued elements. This eliminates the need to shift elements forward after each dequeue operation‚ significantly improving performance. Key to this functionality is maintaining pointers to both the front and rear of the queue‚ and using modular arithmetic to handle the wrap-around effect.

This approach maximizes memory utilization and avoids the wasted space inherent in a simple queue. However‚ implementing a circular queue requires careful management of the front and rear pointers to correctly identify full and empty states.

Priority Queue: Elements Based on Priority

Unlike standard queues adhering to FIFO‚ a priority queue serves elements based on their assigned priority. Higher-priority elements are dequeued before lower-priority ones‚ regardless of their insertion order. This makes priority queues ideal for scenarios where certain tasks or data require immediate attention.

Implementation often involves using a heap data structure‚ specifically a min-heap or max-heap‚ to efficiently manage the priority order. A min-heap ensures the element with the lowest priority is always at the root‚ while a max-heap places the highest priority element at the root.

Operations like insertion and deletion maintain the heap property‚ guaranteeing that the highest (or lowest) priority element is readily accessible. Priority queues find applications in task scheduling‚ event simulation‚ and graph algorithms like Dijkstra’s algorithm.

Dequeue (Double-Ended Queue): Operations from Both Ends

A dequeue‚ short for double-ended queue‚ represents a versatile extension of the traditional queue concept. Unlike queues that restrict insertion at the rear and deletion from the front‚ a dequeue allows operations at both ends – the front and the rear – offering greater flexibility.

This dual functionality enables adding and removing elements from either side‚ making it suitable for scenarios requiring operations like reversing a queue or implementing algorithms that benefit from access to both ends. Dequeues can be implemented using either arrays or linked lists‚ each with its own performance characteristics.

Applications include managing undo/redo stacks‚ implementing job scheduling systems‚ and serving as a building block for more complex data structures. The ability to operate from both ends makes the dequeue a powerful tool in various programming contexts.

Implementing Queues

Queues can be efficiently realized using either array or linked list implementations‚ each offering distinct advantages regarding memory usage and operational speed.

Array Implementation of Queues

Implementing a queue using an array involves allocating a contiguous block of memory to store the queue elements. A key aspect is maintaining two pointers: front‚ indicating the index of the first element‚ and rear‚ pointing to the index where the next element will be inserted. Initially‚ front and rear are often set to -1‚ signifying an empty queue.

Enqueueing an element involves incrementing rear and then placing the new element at array[rear]. Dequeueing requires retrieving the element at array[front] and then incrementing front. However‚ a simple array implementation can lead to inefficiencies. When rear reaches the end of the array‚ it needs to wrap around to the beginning‚ creating a circular queue to avoid wasted space.

A potential drawback is the fixed size of the array‚ which might necessitate resizing if the queue grows beyond its initial capacity. This resizing operation can be computationally expensive‚ involving allocating a new array and copying elements.

Linked List Implementation of Queues

Utilizing a linked list to implement a queue offers a dynamic alternative to arrays‚ circumventing the limitations of fixed size. In this approach‚ each element of the queue is stored within a node of the linked list. The queue maintains pointers to both the front (head) and rear (tail) of the list;

Enqueueing involves creating a new node‚ assigning it the element’s value‚ and appending it to the rear of the linked list. This is typically an O(1) operation. Dequeueing‚ conversely‚ removes the node at the front‚ updating the front pointer to the next node in the list‚ also generally O(1).

Unlike array implementations‚ linked lists don’t require resizing‚ providing flexibility in handling varying queue sizes. However‚ accessing elements requires traversing the list‚ potentially making access slower than array-based queues. Memory allocation for each node also introduces overhead.

Applications of Queues

Queues are vital in operating systems for scheduling‚ breadth-first search algorithms‚ managing printer tasks‚ and efficiently handling requests within web server environments.

Operating System Scheduling

Operating systems heavily rely on queues to manage processes and threads vying for CPU time. When multiple processes are ready to execute‚ they are typically added to a ready queue. This queue ensures fairness by serving processes in the order they arrived – a classic First-In‚ First-Out (FIFO) approach.

Different scheduling algorithms utilize queues in various ways. For instance‚ Round Robin scheduling employs a circular queue‚ giving each process a fixed time slice before moving to the next. Priority scheduling might use a priority queue‚ where processes with higher priority are dequeued before others.

I/O requests are also often managed using queues. When a process requests access to a device (like a disk)‚ the request is placed in an I/O queue. The operating system then services these requests in a queued manner‚ optimizing device utilization and preventing conflicts. Effectively‚ queues are the backbone of multitasking and resource allocation within an OS.

Breadth-First Search (BFS) Algorithm

Breadth-First Search (BFS) is a graph traversal algorithm that systematically explores a graph level by level. Crucially‚ it utilizes a queue to manage the order of node visits. Starting at a designated root node‚ BFS enqueues this node and then dequeues it‚ visiting all its unvisited neighbors before moving to the next level.

The queue ensures that nodes closer to the root are visited before those further away‚ hence the “breadth-first” nature. As each neighbor is discovered‚ it’s enqueued for later exploration. This process continues until all reachable nodes have been visited or the target node is found.

BFS is widely used in finding the shortest path in unweighted graphs‚ network routing‚ and crawling web pages. The queue’s FIFO property guarantees that the first node added is the first one explored at each level‚ making it ideal for these applications.

Printer Queues and Task Management

Printer queues represent a classic real-world application of queues in computer science. When multiple documents are sent to a printer simultaneously‚ they aren’t printed instantly. Instead‚ they are added to a queue – a FIFO structure – where the first document submitted is the first one printed.

This prevents chaos and ensures fair access to the printer. Similarly‚ operating systems employ queues for task management. Processes waiting for CPU time are often placed in a ready queue. The scheduler then dequeues processes‚ granting them CPU access based on priority or arrival order.

Queues are also vital in managing print jobs‚ handling incoming requests‚ and scheduling tasks‚ ensuring efficient resource allocation and preventing system overload. This demonstrates the practical utility of queues beyond theoretical computer science.

Handling Requests in Web Servers

Web servers heavily rely on queues to manage incoming client requests efficiently. When a server receives numerous requests concurrently – for web pages‚ images‚ or data – it doesn’t process them all at once. Instead‚ these requests are placed into a queue‚ ensuring orderly processing.

This queuing mechanism prevents the server from becoming overwhelmed and maintains responsiveness. The server dequeues requests one by one‚ processes them‚ and sends back the appropriate responses. This FIFO approach guarantees that requests are handled in the order they were received‚ providing a fair service.

Without queues‚ web servers would struggle to handle peak loads‚ leading to slow response times or even crashes. Queues are‚ therefore‚ a critical component of robust and scalable web infrastructure‚ ensuring a smooth user experience.

Queue Complexity Analysis

Enqueue and dequeue operations typically exhibit O(1) time complexity‚ while space complexity depends on the chosen implementation – arrays or linked lists.

Time Complexity of Enqueue and Dequeue

Understanding the time complexity of fundamental queue operations – enqueue (adding an element) and dequeue (removing an element) – is crucial for evaluating performance. In most standard queue implementations‚ both enqueue and dequeue boast an impressive O(1) time complexity. This signifies that the time taken to perform these operations remains constant‚ irrespective of the queue’s size.

However‚ it’s important to acknowledge that this optimal performance hinges on utilizing efficient underlying data structures like linked lists or dynamically resizing arrays. A poorly implemented queue‚ perhaps using a static array without proper management‚ could degrade to O(n) complexity for dequeue‚ requiring shifting of elements.

Therefore‚ when selecting a queue implementation‚ prioritize those designed for constant-time enqueue and dequeue operations to ensure scalability and responsiveness in your applications. This efficiency makes queues exceptionally well-suited for scenarios demanding rapid processing of elements in a first-in‚ first-out manner.

Space Complexity of Queue Implementations

The space complexity of a queue is determined by the amount of memory it requires to store its elements. This varies depending on the chosen implementation method. When utilizing a dynamic array‚ the space complexity is typically O(n)‚ where ‘n’ represents the number of elements currently stored within the queue. This is because the array dynamically expands as new elements are added‚ consuming additional memory.

Conversely‚ a queue implemented using a linked list also exhibits a space complexity of O(n). Each element in the linked list occupies memory for both the data itself and a pointer to the next element. However‚ linked lists offer the advantage of allocating memory only as needed‚ avoiding the potential for wasted space associated with pre-allocated arrays.

Therefore‚ both common implementations demonstrate linear space complexity‚ scaling directly with the number of elements. Careful consideration of potential queue size is vital for efficient memory utilization.